NG2 cells (an intro)

Before I forget all I learned, I’d like to put up a series of posts around the research I was doing in Bonn. Slightly glia-centric (on OPCs / NG2 cells + methods) and hopefully interesting to those working primarily with neurons!

I only realised in trying to write this that my ability to write “simply” (ELI5 in a way) has completely gone out of the door for practice. I tried it here, but perhaps it resembles the mad ravings of someone who indeed, was in that German basement lab too long ……

( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

Aaaand off we go on post #1

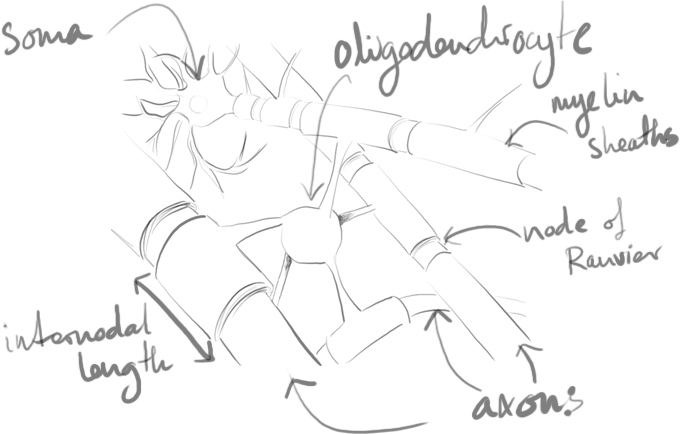

Myelin plasticity is an emerging field impacting our understanding of neural plasticity and the circuit-level activity patterns within the brain. The thickness and internodal lengths defining myelin sheath effectiveness are essential in tuning the conduction velocity of action potentials.

Studies have shown that myelin varies according to required conduction speeds1 and changes to reflect environment and neuronal activity2–7. Without an understanding of myelination and the dynamic way oligodendrocytes perform this task, our understanding of the development and maintenance of the nervous system is likely incomplete.

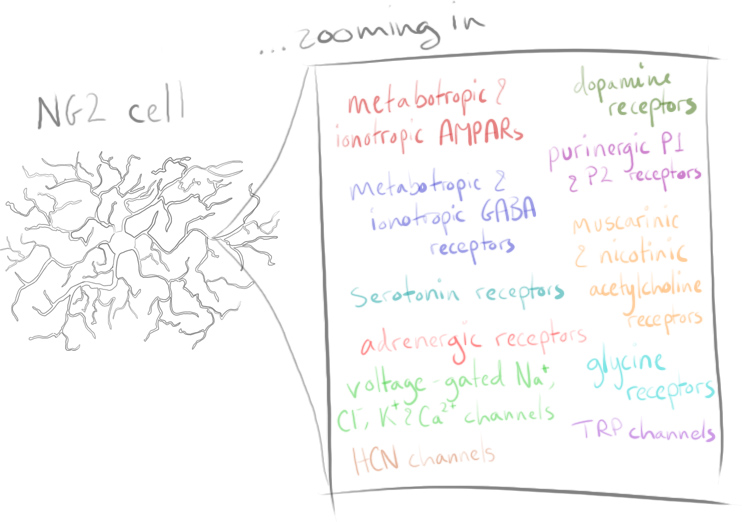

Oligodendrocytes are a type of glial cell thought to be generated solely from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), otherwise known as NG2 cells. These NG2 cells have been recognised as a unique type of glial cell due to their possession of neuron-glial synapses along with an abundance of voltage-gated ion channels8. As yet, what informs and influences NG2 cells to myelinate specific axons is not known. The influence of glutamatergic (and perhaps GABAergic) signalling to these cells is temptingly thought to convey information about where and when to myelinate9,10.

Identified and so named due to their strongly expressed neural/glial antigen 2, NG2 cells are a resident proliferating glial population comprising around 5% of mammalian CNS cells11. Primarily originating from the discrete ventral domains in the spinal cord and ventral subpallial regions of the forebrain during embryonic development, NG2 cells migrate and eventually populate all brain regions12,13.

Some NG2 cell populations appear to give rise to astrocytes14,15 and deep-layer interneurons in areas such as the dorsal cortex16. Other postnatally arising NG2 cells from the subventricular zone are known to form classical oligodendrocytes. At present fate-mapping studies, genetic CRE/loxP lineage tracing and BrdU+ studies have not fully ascertained the differences between progenitor pools, nor whether they give rise to distinct populations17,18.

Lets go into the history a little…

NG2 neuron-glial synapses were first suggested by Bergles in 200019. We now understand these synapses to have facilitation and depression, fast activation and quantized responses that are fairly typical for neuron-neuron synapses.

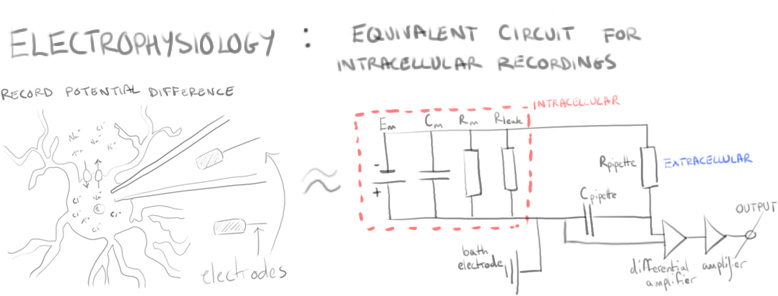

In Bergles’ initial study, electrophysiological NG2 cell recordings in the hippocampus of mouse brains were examined in response to neuronal stimulation.

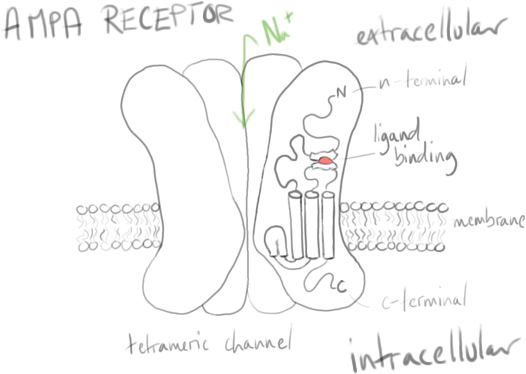

Excitation (depolarisation) of neurons in synaptic transmission uses some important receptors, with α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs) being known for their fast synaptic transmission in response to glutamate as well as for their role in long-term potentiation (LTP).

Bergles & co wanted to understand how glutamate was transmitted and affected the AMPA receptors on NG2 cells: Often other glial cells in the brain were affected by glutamate from diffusion, or from reverse transport via neuronal axons. What mechanism was at work here?

Using paired stimuli of afferent excitatory neurons and recording NG2 cell responses showed something akin to paired pulse facilitation. That is, in short, a type of short term synaptic plasticity where the second evoked response is increased.

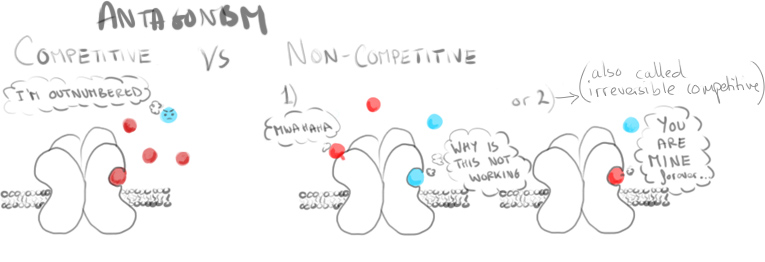

Recorded responses were increased and slowed by a drug known to potentiate AMPARs (cyclothiazide), inhibited by an AMPAR antagonist (GYKI) and stopped entirely when calcium release was inhibited (by adding Cd2+).

These responses showed activation of NG2 cell AMPA receptors, but not due to reverse transport of glutamate from the neurons. Looking further, some of these AMPARs were seen to be permeable to calcium. (Observed when receptors lacking the GluR2 subunit are blocked by endogenous intracellular polyamines such as spermine, or the currents inhibited by selective antagonists such as the Joro spider toxin).

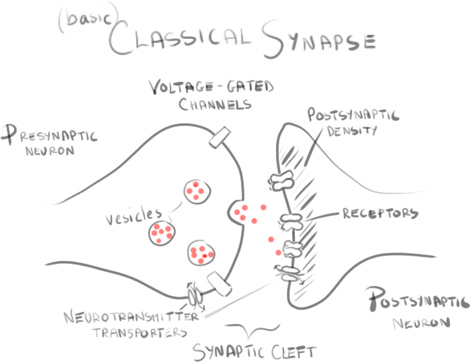

Knowing all this it’s worth asking – are glutamatergic synapses present? To know that, they needed to know whether NG2 cells received vesicles filled with glutamate, as typically occurs in neuronal synapses.

Miniature excitatory postsynaptic potentials (mEPSPs), tiny depolarisations, occur without neurons firing action potentials. They are the spontaneous fusion of vesicles containing neurotransmitters such as glutamate and result in variable, fast depolarisations of the membrane in neurons. Examining NG2 cells and the presence or lack of these signals would be highly suggestive.

In NG2 cells (excitingly) similar such currents could be seen.

These little currents were tested; what happens if the number of vesicles released from the nerve terminals is increased? Using toxins such as the presynaptic neurotoxin pardaxin it could be seen that NG2 cells then experienced high frequency bursts of mEPSPs very similar to neurons. Indeed, NG2 cells encountered quantal glutamate-filled vesicles.

Electron microscopy studies then showed axon terminals to have synaptic junctions with NG2 cells. With a high clustering of vesicles from the presynaptic neurons and a noticeable (though thinner than on spines) postsynaptic density, NG2 cells have distinct neuron-glial synapses.

What is the effect of these synapses on NG2 cells? Why are they useful?

There are many ideas in the mix. While most of them focus on either inhibiting or encouraging differentiation and subsequent myelination, we’ll look at a couple of other options below.

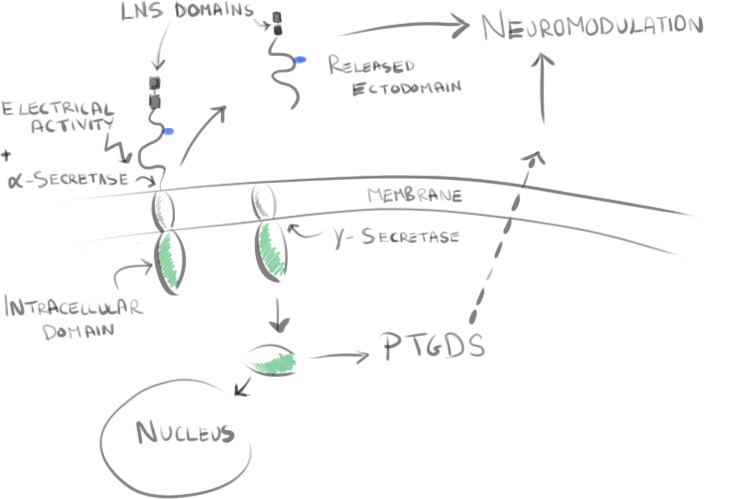

One such idea shown in the work of Trotter et al20,21 is that neuronal activity stimulates the cleavage of the NG2 transmembrane proteoglycan. Some cleaved parts of this protein may then influence prostaglandin D2 synthase (PTGDS) expression, resulting in neuromodulatory effects. Other cleaved parts such as the LNS domain may impact anchoring within the extracellular matrix and can influence postsynaptic signalling and glutamatergic signalling within the network.

Another idea is that synapses may alter downstream processes, but are ultimately not required for myelination. Myelination can still occur onto fixed axons or even nanofibers of a particular length22,23. It may be that potassium gradients influence differentiation to myelinating oligodendrocytes24, or simply that NG2 cells follow a program of differentiation without exogenous signalling required.

While unspecified myelination may occur in vitro without signalling, the specificity of myelinated vs unmyelinated axons in the brain is another matter. Axons that could be myelinated are not, and those which can be myelinated are seemingly fine-tuned for conduction velocity. This suggests neuronal signalling plays a determining role in this.

Whether it occurs via changes in intracellular calcium, via feedback loops by modulatory factors, or by an as-yet undiscovered cascade, we do not know. There is a lot of exciting research being done including on the effect of learning on myelination and on the many other channels and receptors of the cell. There is a lot of look forward to in the field of glia and the critical roles they play. Slowly, we are beginning to see them as more than the cerebral glue of the brain.

References

1. Ford, M. C. et al. Tuning of Ranvier node and internode properties in myelinated axons to adjust action potential timing. Nat. Commun. 6, 8073 (2015).

2. Gibson, E. M. et al. Neuronal Activity Promotes Oligodendrogenesis and Adaptive Myelination in the Mammalian Brain. Science (80-. ). 344, 1252304–1252304 (2014).

3. Gautier, H. O. B. et al. Neuronal activity regulates remyelination via glutamate signalling to oligodendrocyte progenitors. Nat. Commun. 6, 8518 (2015).

4. Etxeberria, A. et al. Dynamic Modulation of Myelination in Response to Visual Stimuli Alters Optic Nerve Conduction Velocity. J. Neurosci. 36, 6937–48 (2016).

5. Hines, J. H., Ravanelli, A. M., Schwindt, R., Scott, E. K. & Appel, B. Neuronal activity biases axon selection for myelination in vivo. 18, (2015).

6. Sampaio-Baptista, C. et al. Motor skill learning induces changes in white matter microstructure and myelination. J Neurosci 33, 19499–19503 (2013).

7. Mensch, S. et al. Synaptic vesicle release regulates myelin sheath number of individual oligodendrocytes in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 628–630 (2015).

8. Larson, V. A., Zhang, Y. & Bergles, D. E. Electrophysiological properties of NG2+ cells: Matching physiological studies with gene expression profiles. Brain Res. 1–23 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.010

9. Angulo, C. & Fields, R. D. Nonsynaptic junctions on myelinating glia promote preferential myelination of electrically active axons. (2015). doi:10.1038/ncomms8844

10. Wake, H., Lee, P. R. & Fields, R. D. Control of local protein synthesis and initial events in myelination by action potentials. Science 333, 1647–51 (2011).

11. Dawson, M. R. L., Polito, A., Levine, J. M. & Reynolds, R. NG2-expressing glial progenitor cells: An abundant and widespread population of cycling cells in the adult rat CNS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 24, 476–488 (2003).

12. Trotter, J., Karram, K. & Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells: Properties, progeny and origin. Brain Res. Rev. 63, 72–82 (2010).

13. Hill, R. a. & Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells (polydendrocytes): Listeners to the neural network with diverse properties. Glia 62, 1195–1210 (2014).

14. Zhu, X., Hill, R. a & Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells generate oligodendrocytes and gray matter astrocytes in the spinal cord. Neuron Glia Biol. 4, 19–26 (2008).

15. Zhu, X., Bergles, D. E. & Nishiyama, A. NG2 cells generate both oligodendrocytes and gray matter astrocytes. Development 135, 145–157 (2008).

16. Tsoa, R. W., Coskun, V., Ho, C. K., de Vellis, J. & Sun, Y. E. Spatiotemporally different origins of NG2 progenitors produce cortical interneurons versus glia in the mammalian forebrain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 7444–9 (2014).

17. Marques, S. et al. Oligodendrocyte heterogeneity in the mouse juvenile and adult central nervous system. Science (80-. ). 352, 1326–1329 (2016).

18. Huang, W. et al. Novel NG2-CreERT2 knock-in mice demonstrate heterogeneous differentiation potential of NG2 glia during development. Glia 62, 896–913 (2014).

19. Bergles, D. E., Roberts, J. D., Somogyi, P. & Jahr, C. E. Glutamatergic synapses on oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus. Nature 405, 187–191 (2000).

20. Sakry, D., Yigit, H., Dimou, L. & Trotter, J. Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells Synthesize Neuromodulatory Factors. PLoS One 10, e0127222 (2015).

21. Sakry, D. & Trotter, J. The role of the NG2 proteoglycan in OPC and CNS network function. Brain Res. 1–6 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.003

22. Bechler, M. E., Byrne, L. & Ffrench-Constant, C. CNS Myelin Sheath Lengths Are an Intrinsic Property of Oligodendrocytes. Curr. Biol. 25, 2411–2416 (2015).

23. Lee, S., Chong, S. Y. C., Tuck, S. J., Corey, J. M. & Chan, J. R. A rapid and reproducible assay for modeling myelination by oligodendrocytes using engineered nanofibers. Nat. Protoc. 8, 771–782 (2013).

24. Maldonado, P. P. & Angulo, M. C. Multiple Modes of Communication between Neurons and Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells. Neuroscientist 1–11 (2014). doi:10.1177/1073858414530784