Abstract Concepts

The few times I snuck into philosophy lectures during university I remember being confused. Not so much by the philosophical terminology (having spent a good few years in the larceny of my older sister’s philosophy anthologies) but by the unblinking acceptance that when saying something like the term “qualia” or “liberty” or “freedom” we understand it in the same way.

Now Qualia is a somewhat abstract concept in itself. It is the idea of subjective conscious experience – the taste of red wine, the colour of a turquoise sea. A property that can only be understood by direct experience – the unique individual moment of apprehending something via your consciousness. Arguments in this field say that experiencing some qualia – say, your nose being tickled by a buttercup – can’t be dissected by reductionist science, but instead reflects the subjective quality, the ‘what it’s like to feel your nose tickled’ aspect of consciousness.

This kind of concept can be likened to the concept of freedom. It encompasses a wide range of ideas, emotions and experiences. It’s vague, and doesn’t just have one action or physical reality to underpin it: just as the concept of qualia might be “whether a duck experiences the qualia of it’s pond” or “how I feel sitting here writing about it”, freedom can be “the ability of Obama to move his little big toe”, “a historical perspective of African slavery” or “my qualia of sitting here feeling free to think what I choose”. It is abstract.

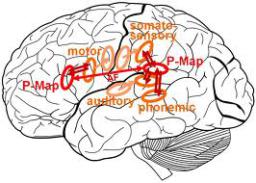

This fuzzyness always made me wonder how we interpret these concepts in the brain. After all, it isn’t quite as simple as reading the phrase “a boy threw a ball”: here we have two nouns of which we have fairly certain experiences of encountering, and a motor action which we've employed. We can easily imagine a physical representation, and we’ll probably even have a mental representation of a boy throwing a ball in our heads, a mishmashed compendium of all the balls, boys and throwing that our qualia has given us. Our brain’s reaction to such concrete concepts is quite easy to model by fMRI. When we read the phrase, our sensorymotor complex is activated and we replay the action of throwing the ball with our motor neurons. Interestingly but not surprisingly, different parts of our brain are activated according to differing sensation: on “hearing a chime” our audio neurones, on “seeing a flower” visual and “eating a millefeuille” gustatory. Likewise corresponding parts of our sensorymotor map are activated when reading “hands”, “feet” and so forth.

Curiously, emotional valence can be grounded in the physical embodiment of our actions whilst still being largely motor-neuron reflections in the brain. Research studies show that we feel more positive about a topic when we see or do a ‘thumbs up’ sign. Likewise we feel more negative with a ‘thumbs down’. For feelings of happiness, we can alter our emotional response to positive by putting a pen between our teeth, forcing a grin – alternately feel more negative by holding the pen with our lips (and so a more sallow, puckering expression). By putting up or seeing the middle finger raised, we find the content of our browsing material more offensive.

This emotion-motor neuron link is surprisingly strong. You can find that by paralysing the facial muscles, we experience a lower level of emotional reaction to watching shows such as theatre or dance. It’s almost like it’s necessary to experience what we see for ourselves in order for the mind to experience it fully. A similarity can be seen in the speed with which we process action-reading. For interpreting the meaning and verifying a phrase such as “John threw the ball away”, we do this faster when moving our hands in a gesture away from ourselves – likewise for “John caught a ball” we comprehend faster when mimicking a “catching” gesture. With the interest in mirror neurons (see Ramachandran’s work for a good exploration + TED talk) it isn’t surprising that emotion and cognition speed relates with motor neurons – there is even strong speculation that empathy is a result of these mirror neurons, and results that suggest increased exposure to varying emotions (e.g. by the medium of reading the fantasy genre) increases our empathic awareness and ability to process others’ wants.

A sidestep from all this, let us return to the field of abstract concepts. How we do we process a concept that doesn’t have a concrete physical manifestation, when we attribute emotional links and memories as part of its definition? How do we see freedom? Or how do we feel it/hear it/imagine it?

By scanning the brains of numerous victims whilst haranguing them with words, there is an answer (of sorts). Like most things, abstract concepts are also grounded in sensorymotor experiences. Though we might expect an abstract concept to show an elaborate weave of connections in the brain – for example we may expect ‘power’ to resonate through emotional processing, abstract thinking, logic and motor to reflect ideas such as ‘self-powerless’, ‘banking’ and ‘lift’, in actuality such large terms are placed into small boxes, in the context of their utterance.

Though we obviously develop more connections with respect to these ideas, we only light up the part of the brain reflecting the context-dependent meaning. That is, “he powerfully lifted 70kg” wouldn't light up our facial recognition (Whereas “Matthew clenched his jaw powerfully” probably would). Motor activation is context dependent, and abstract concepts help frame how we experience a scenario – but they don’t seem to define it.

References:

Pecher, D., Boot, I., & Dantzig, S. Van. (2011). Abstract Concepts : Sensory-Motor Grounding , Metaphors , and Beyond. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (1st ed., Vol. 54, pp. 217–248). Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385527-5.00007-3

Sakreida, K., Scorolli, C., Menz, M. M., Heim, S., Borghi, A. M., & Binkofski, F. (2013). Are abstract action words embodied? An fMRI investigation at the interface between language and motor cognition. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 7(April), 125. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00125

Schuil, K. D. I., Smits, M., & Zwaan, R. a. (2013). Sentential context modulates the involvement of the motor cortex in action language processing: an FMRI study. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 7(April), 100. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00100